Forever Ideas, Forever Books: The Deep Springs of Ford's Political Wisdom

Before my series of interviews with President Ford in 2005, I had read the 1976 Republican Party platform on which the incumbent ran and also his political autobiography, A Time to Heal, which came out in 1979. Both source documents gave me a better understanding of Ford's political thought, but they also raised questions I wanted to explore. I was especially keen to learn what body of wisdom lay behind his political principles.

In his memoirs, Ford declared he was running for President in 1976 on five organizing principles that were consistent with the American founding that citizens were then celebrating: (1) increased freedom for all Americans from the encroachments of an ever-expanding federal government; (2) the preservation of America's free enterprise system; (3) fiscal responsibility that restrained Congress; (4) a strong national defense; and (5) affirmation of the rights and responsibilities of state and local governments.

These organizing principles provide a snapshot of Ford's mature political thought in 1976, when he was not only running for President but also leading the nation in her bicentennial celebration of the Founders' achievement. The principles seem straightforward enough, even formulaic, but in conversation with the President I soon discovered that there was more to them than meets the eye. It turns out that Ford's political principles were richly informed not only by Republican platforms, but also by (1) his midwestern upbringing, (2) his formal undergraduate and legal education, (3) world war, (4) his experience in the political arena, (5) his knowledge of our nation's history, and (6) the wisdom of ancient writers.

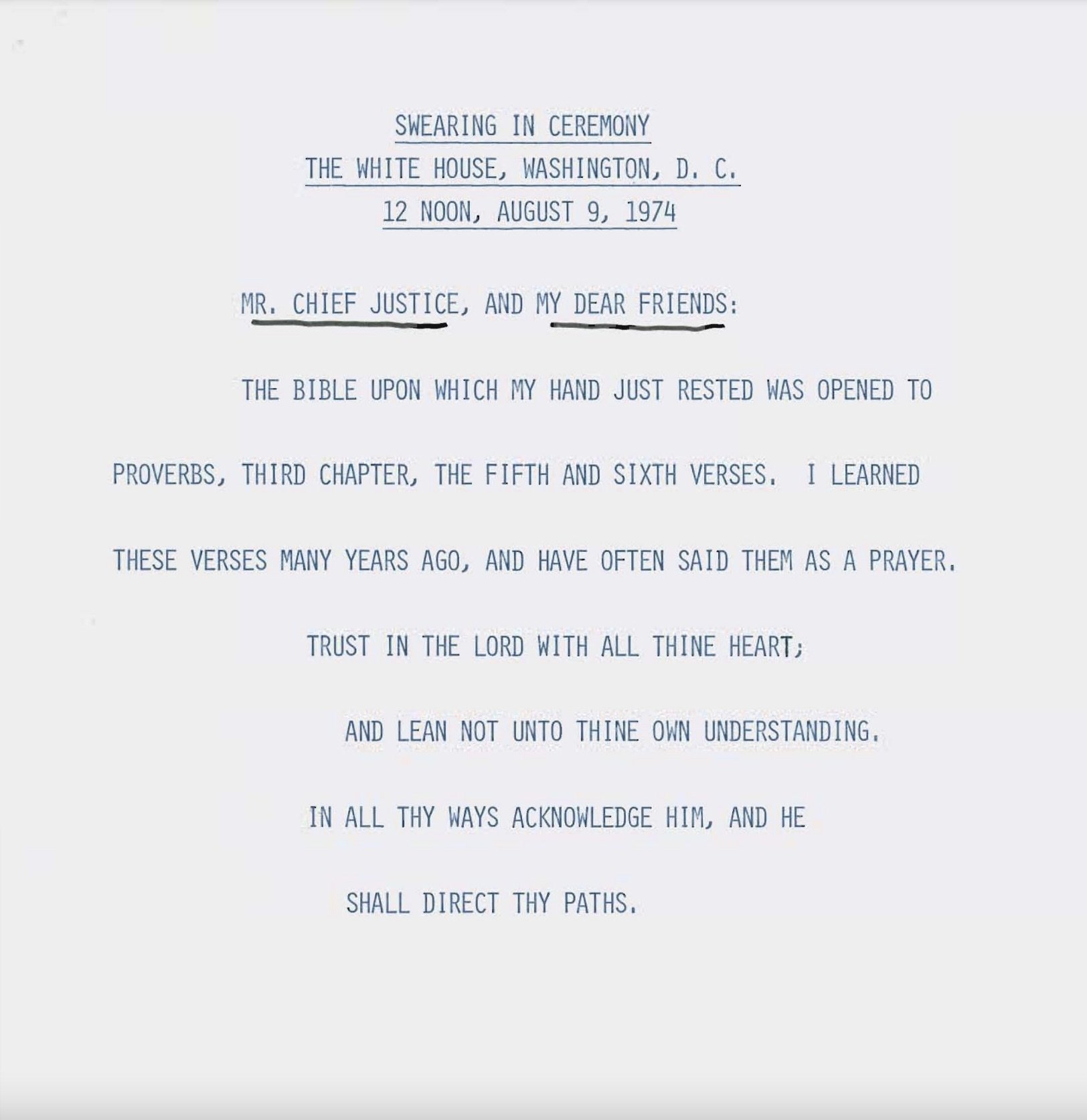

As the above list implies, the 38th President had much greater depth when discussing political principles than is usually assumed. True, he had to be prompted by questions that would draw him out: he did not wear his political philosophy on his sleeve, just as he did not wear his religious faith there, either. But once prompted, I found him ready to speak at length when I asked him to compare his political principles to, say, those of Ronald Reagan (who contested Ford for the presidency in 1976 and in so doing left a festering bur under his saddle).

Take, for example, fiscal restraint. Ford refused to agree with the conventional wisdom that Reagan was more conservative than he, especially when it came to fiscal matters. The 38th President was proud of the fact that he was the last chief executive who could take the federal budget home without needing aides to interpret it for him. Because of the technical knowledge he acquired over many years on Appropriations, he knew he could propose a more responsible budget and at the same time rein in spending better than his rival could.

Or consider a strong national defense. The 38th President was proud of the advanced defense systems he supported during his time in the Oval Office to keep America strong in a dangerous world. There was no way he took a back seat to Reagan on this point.

Moreover, even though Ford had spent more than a quarter-century in Washington, he fully supported the Tenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution that made state government the default level of government: "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." Again, Reagan was not going to outflank Ford's right when it came to respect for state and local government.

Ford then went on to tell me that every major influence on his life committed him to the political foundations on which America was built. As a lawmaker, he became attentive to our nation's state papers. He had been exposed to some of America's state papers in his history classes at the University of Michigan and also in his law classes at Yale. He also had heard select quotations from these state papers countless times during political career--mostly on the floor of the House but also in campaign stump speeches. So in 1976, it should come as no surprise that he would self-consciously align his political principles to "the spirit of '76." America's strongest roots were anchored in bedrock formed by the rich strata of Lincoln's speeches, Bill of Rights, Federalist Papers, U.S. Constitution, Northwest Ordinance, and Declaration of Independence.

In my interview with him, Ford brushed off the notion that he was any kind of scholar. He joked that he got most of his history education from the scores of monuments and statues in Washington, DC, he walked by--in addition to the hundreds of rubber-chicken Lincoln Day events he had attended on the campaign trail!

There is some truth in the quip. Washington, DC, honors the founders in countless ways. When President Ford led Americans in their celebration of the bicentennial and the Founders' world-historic achievement, among the touch points celebrated were the great state papers he has studied: the Declaration, Northwest Ordinance, Constitution, Bill of Rights, and Lincoln's speeches. A number of passages from these documents are literally engraved on walls and plinths.

One principle Ford encountered again and again among the Founders, especially as he and his staff prepared for America's bicentennial with the help of Daniel Boorstin, the Librarian of Congress he had appointed, was their belief in the necessity of virtue in self-government. It was not enough that the new government's federal structure and checks and balances thwarted tyranny. Ultimately it was the citizens' virtue that thwarted tyranny. James Madison wrote in Federalist 55 that our Constitution depends on “sufficient virtue among men for self-government”; otherwise, “nothing less than the chains of despotism can restrain them from destroying and devouring one another.” George Washington in his Farewell Address opined, "Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, Religion and morality are indispensable supports." Similarly, John Adams argued in a letter: “We have no Government armed with Power capable of contending with human Passions unbridled by morality and Religion.... Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.”

We've reviewed the political principles of the Founders that informed Ford's own understanding. Let's now look deeper into the sources that informed the founding generation's political principles.

Virtue is the bridge between the Founders and their culture, and an even older culture. Indeed, when we look deeper into the past, back behind the culture that informed the American founding, we discover the remarkable cultures of early modern Britain, medieval Europe, ancient Rome, classical Greece, and the Holy Land. In the 2005 interviews, I asked Ford if he knew the work of a fellow Michigander and conservative author, Russell Kirk, who lived just sixty miles from where Ford grew up and wrote about Western, medieval, and ancient civilizations. Ford recalled some letters they had exchanged but said he was not as familiar with Kirk's work as he wanted to be. But both men respected virtue-anchored leadership and the culture that supported it.

The logic of my argument goes back to Aristotle's law of identity: If a = b, and b = c, then a = c. That is to say, if Ford's platform is closely aligned with the American Founding, and if the American Founding is closely aligned with the ancient wisdom of Europe, then Ford's platform is aligned with the ancient wisdom of Europe.

My argument is not that Ford was a political philosopher. He was not. He was more a man of action than a man of reflection. His entire career was spent in the arena, not the study. But because of his legal training and political career, he had more than a passing familiarity with America's state papers and the culture that informed them. Those state papers and the culture that informed them would shape Ford's strongly held political principles, principles it would be well to resurrect today.