Hannah Arendt and the Dangers of “Inner Emigration”

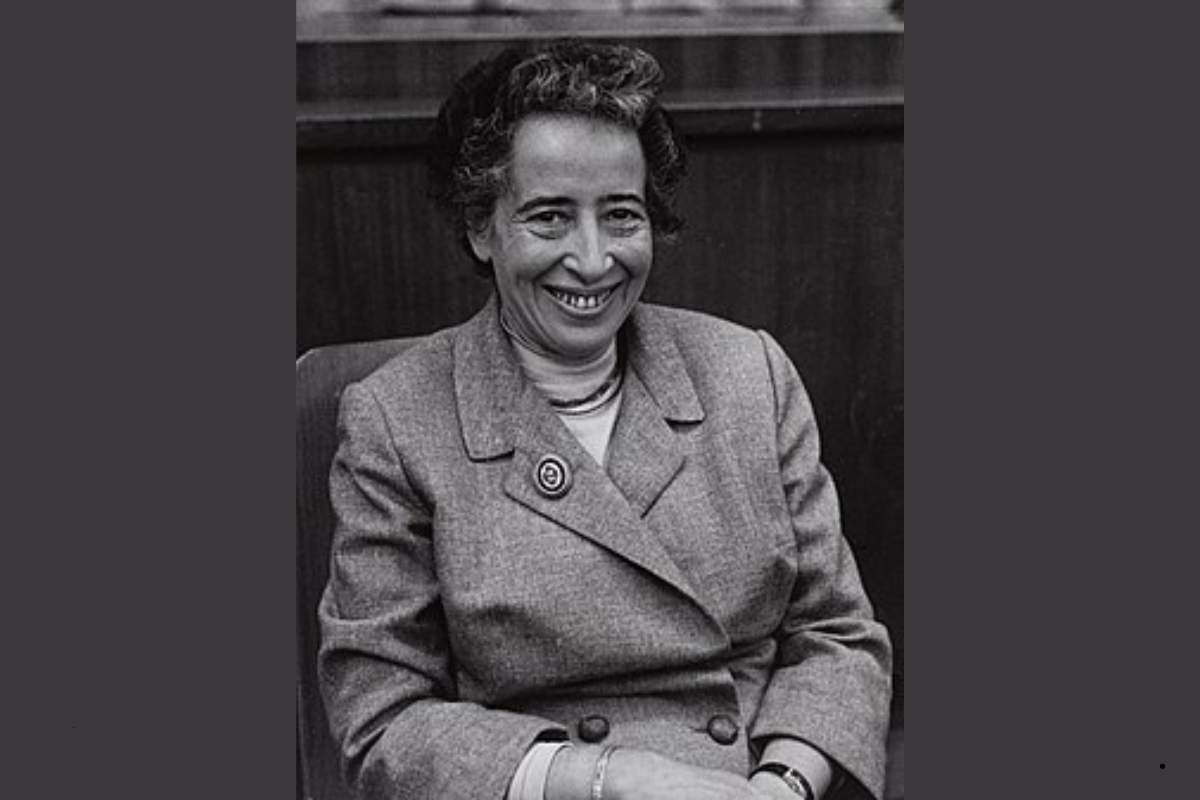

Image Courtesy: Barbara Niggl Radloff, CC BY-SA 4.0

In the past, I used to grab my morning tea and then check the news. Now, I wake up and dread the morning’s political news. I am not alone in wanting to withdraw from politics; I hear this sentiment from both sides of the political spectrum. People are tired of it all and want to ignore the effects of recent decisions. For me, I crave a stable government that I don’t have to worry about constantly. What difference does it make if I know, for example, the effect of the withdrawal of funding for USAID on children globally? Sometimes, when I know people will suffer, I want to look away and not know about it. Wouldn’t my life be happier if I ignored what is happening nationally and globally? However, Hannah Arendt’s admonitions always draw me back to political awareness.

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) studied philosophy in Germany as a student of the influential philosopher Martin Heidegger. When the Nazis came to power in the 1930s, many people at risk emigrated from Germany. Arendt, a young Jewish intellectual, lived in Germany until police jailed her for underground activism in 1933. After her first arrest, she fled to France but soon thereafter was imprisoned in a Jewish internment camp, from which she escaped to Marseilles. After a harrowing trip through Spain, she got a visa to the United States, where she became a stateless person without formal citizenship in any country. Although Arendt was forced to flee physically, others, perhaps not in the same mortal danger, also fled by withdrawing emotionally and intellectually, choosing to retreat from the public realm.

Withdrawing into private life was an escape that Arendt called “inner emigration,” a withdrawal into an interior realm, looking away from public realities. I admit I feel tempted by inner emigration in today’s world, as do many others who want to retreat from the daily onslaught of news. Arendt said that physical flight “in dark times of impotence” may be justified “as long as reality is not ignored” (1955, 22). However, as seductive as inner emigration may be, Arendt believed that turning away from our shared public community results in losing an essential part of being human.

Arendt’s analysis of life in a totalitarian regime comes from her personal experience. She wrote about the “dark times” of 1930s Germany when she experienced the “highly efficient talk and double-talk of nearly all official representatives” (1955, viii); when, she said, “everybody is swept away unthinkingly by what everyone else does and believes in...” (1971, 192). In dark times, she said, evil is built into the practices and conventions of ordinary life, and social norms can become dangerous and destructive. Fascist propaganda “was not satisfied with lying, but deliberately proposed to transform its lies into reality” (1945, 146-47). No one was prepared for such a thorough fabrication of an untrue reality. It was a time when leaders degraded “all truth into meaningless triviality” (1955, viii). The support of totalitarian regimes, especially when the public could be aware of its atrocities, made Arendt wonder how a mostly educated population (60% of the SS had college degrees) shielded itself from critically examining what was happening in their country.

With Arendt, I wonder why we should continue to be aware and active politically in a world where one feels powerless. What possible value could the angst of keeping abreast of political news be when it feels like I can’t change anything? Arendt said that radical honesty – facing what is painful to face – is necessary even when one feels politically impotent.

Facing up to reality

Arendt rejected the inclination to withdraw mentally and “simply ignore the intolerably stupid blather of the Nazis” (1955, 23). Because of that withdrawal, good people failed to oppose horrific policies. Totalitarianism, Arendt said, often worked to transform lies into perceived reality. As she later said, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule” is someone “for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist” (1968, 172). As social beings, we may go to extremes to be part of a community with whom we can relate, which could mean overlooking even significant lies. An aspect of our humanness is lost when we accommodate lies and false realities.

Arendt said we need “the unpremeditated, attentive facing up to, and resisting of, reality” (1968, Part One, viii). For Arendt, this meant clearly facing what was happening in the world yet resisting the reality that society and political leaders were constructing for us. Facing reality often necessitates the hard work of conscious resistance. A small example would be the mental energy required to sort out the facts behind competing views in the media. Terror, emotions of passion or patriotism, fervent idealism, uncertainty, or perceived fear of loss can override the type of questioning and discourse that democracy needs. Fear, suspicion, dread, and anger envelop everything when we feel threatened. As we know from history, fear divides us, makes us villainize differences, and suppresses democratic discussion and criticism.

How does one stay aware and conscious when the news leads to fear and anxiety when ignoring or masking reality is so alluring yet damaging to living authentically and morally? Sometimes, we try to protect ourselves by using our everyday busyness to mask knowledge. Alia Malek, of Syrian descent, addresses this in “The Home That Was Our Country: A Memoir of Syria” when she describes Syrian life in 2017. The security force office in her neighborhood was also used as a torture facility. Yet people necessarily went about their everyday lives. She says, “… most insidiously, no matter how much we averted our gaze, the fact that we knew what was happening inside and yet went about our lives made us complicit” (171). She wonders whether she has become an “unwilling collaborator” simply by going about her daily life. Had she and her neighbors become “bit players in the regime’s effort to maintain that everything was normal” (226)? To be clear, Malek is not saying that people should have taken action in that repressive and dangerous regime. Even though she could not change reality, she at least didn’t want to ignore what was happening. The victims are owed our memory. And as Malek and Arendt knew, we must face reality, even when we can’t change it, because denying or ignoring reality is the first step in losing our own moral compass. According to Arendt, each individual’s retreat also results in a demonstrative loss to the world, a loss of the creative illumination that each person could bring into our shared world (1945, 4). Thankfully, most Americans do not live with the type of terror that Malek and Arendt experienced, yet in the onslaught of media, there is much we want to turn away from.

Giving in to the temptation of inner emigration is much easier in our time. Countless lures grab our attention as our phones ding constantly. Email and social media entice us with tragic stories, funny videos, games, and compelling ads designed to hook, addict, and exploit us. As I write this today, understanding what is going on requires focused intentionality when we are bombarded with political changes – when tariffs are constantly changing, when people are fired and then reinstated, when programs are cut and then sometimes refunded, and when the court decides one thing and then changes it the following week. Like many Americans, I often want to give up trying to understand because of the time and energy to cut through the confusion. The onslaught of sensational political headlines makes it challenging to investigate what lies beneath the attention-grabbing stories. The constant news can keep us too busy to even notice that we may have abandoned our social and political obligations, including the duty of careful and critical political thinking.

Arendt doesn’t tell us what is necessary for emotional health when staying aware is painful. She doesn’t tell us how she handled the news about the millions of Jewish people suffering and dying in WWII. However, her words remind us that the courage to stay attentive and be engaged offers the only possibility for future change. As A.J. Muste said about his anti-war protests, even when he couldn’t change the country, he continued to protest at least “so the country won’t change me.” Likewise, staying aware, thinking, and talking with others about what is happening refines our values and cements each of us as citizens.

Arendt, Hannah. 1945/1994. “The Seeds of a Fascist International.” In Essays in Understanding: 1930–1954. Ed. Jerome Kohn. New York: Harcourt Brace and Company. 140–150.

----. 1955. Men in Dark Times. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

----. 1968. Totalitarianism: Part Three of the Origins of Totalitarianism. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

----. 1971/1978. The Life of the Mind. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Malek, Alia. 2017. The Home That Was Our Country: A Memoir of Syria. New York: N.Y. Nation Books.

Judy Whipps is Professor Emerita of Philosophy and Interdisciplinary Studies at Grand Valley State University.

Related Essays